A hazard of the modern age is that I’m never sure if something is normal or if it’s just a weird internet in-joke that everyone will look at me strangely for referencing. I’m pretty sure Harry Harlow’s monkey mother experiment was infamous long before its myriad internet memes, but I’ll offer a quick recap regardless in case you’re not familiar.

The psychologist Dr. Harlow took a bunch of infant rhesus monkeys away from their mothers and raised them in a sterile scientific nursery to study their psychological development. (It was the 1950s, when scientists were completely unburdened by ethics.) It quickly became obvious that raising babies without parents made them turn out sickly and weird. Harlow noticed that the monkeys often hugged the cloth of their diapers (yes, he apparently made them wear diapers) and developed a theory that he set out to test. Thus came the birth of the infamous cloth mother and wire mother.

Harlow’s new sadistic Saw trap was to make the monkeys choose between two maternal effigies: one made of cloth and one made of wire. The infants chose to stay close to the cloth mother under almost all conditions — even when the wire mother was equipped with a milk bottle, and the cloth mother was not. Infants who were only given access to a wire mother had worse developmental outcomes across the board. These findings handily disproved the notion (inexplicably popular among behavioral scientists at the time) that the mother’s role in childcare could basically be reduced to feeding the child. It also illustrated a hazard of allowing only rich white men to practice science, which is that they’ll come up with the most cruel and stupid idea possible, flying in the face of the lived experience of everyone who’s not them, and enshrine it as the 100% totally rational truth of the universe. I’m glad we now allow more people from more diverse backgrounds to practice science so that we can all make our own reductive overgeneralizations.

The wire mother reminds us of the importance of maternal affection — even the facsimile of skin-on-skin contact — in a child’s development. Keeping that context in mind, I’d like to make you wonder why the hell I said all that as I talk about a game I played last month.

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist by Northway Games is a roleplaying game and visual novel. I haven’t talked about video games on this blog yet, so I’ll try to explain the jargon for those who might not be that into this hobby. A roleplaying game is one in which you play a character and grow their skills as you explore the world, making them more competent in certain roles. A visual novel is a text-based story that you read, sort of like a normal book, but the story changes based on the choices your character makes within its world, creating an interactive narrative that can be quite sprawling. It’s not unlike a choose-your-own-adventure book or a tabletop roleplaying game (such as Dungeons & Dragons), but with more sophistication than the former and more structure than the latter. Visual novels also feature art and music to accompany the text, which can definitely make them feel more immersive in some cases. I’ve played several visual novels lately, and while I wish I were reading normal books as well, these games have at least gotten me to read more while I recover from school frying my brain.1

People sometimes criticize visual novels for lacking “real gameplay” — e.g., the tests of hand-eye coordination or tactics that you find in other video games. That’s never been a concern for me, but Exocolonist addresses that perceived gap nicely. Over the course of the game, your character can collect cards that represent significant memories you’ve made. When your decisions lead you to a point with an uncertain outcome, you enter a minigame where you’re challenged to combine those cards in sets, straights, flushes, and other configurations to gain points and achieve a target score. The concept is simple, but various cards have interactions with each other that can yield additional points, and the game can become entertainingly complex. Fans of Wingspan, Magic: The Gathering, and other card-based games might find this familiar.2

I liked the card game, but I was here for the story. A dear friend of mine had told me that I needed to play this game — more than anybody else in our groupchat, apparently, except for another girl who’d already played it — and was so insistent that they actually bought it for me to sweeten the deal. I was curious to know what they’d liked so much about it, and why they’d thought of me specifically. They know me pretty well, so what piece of me did they see in this game?

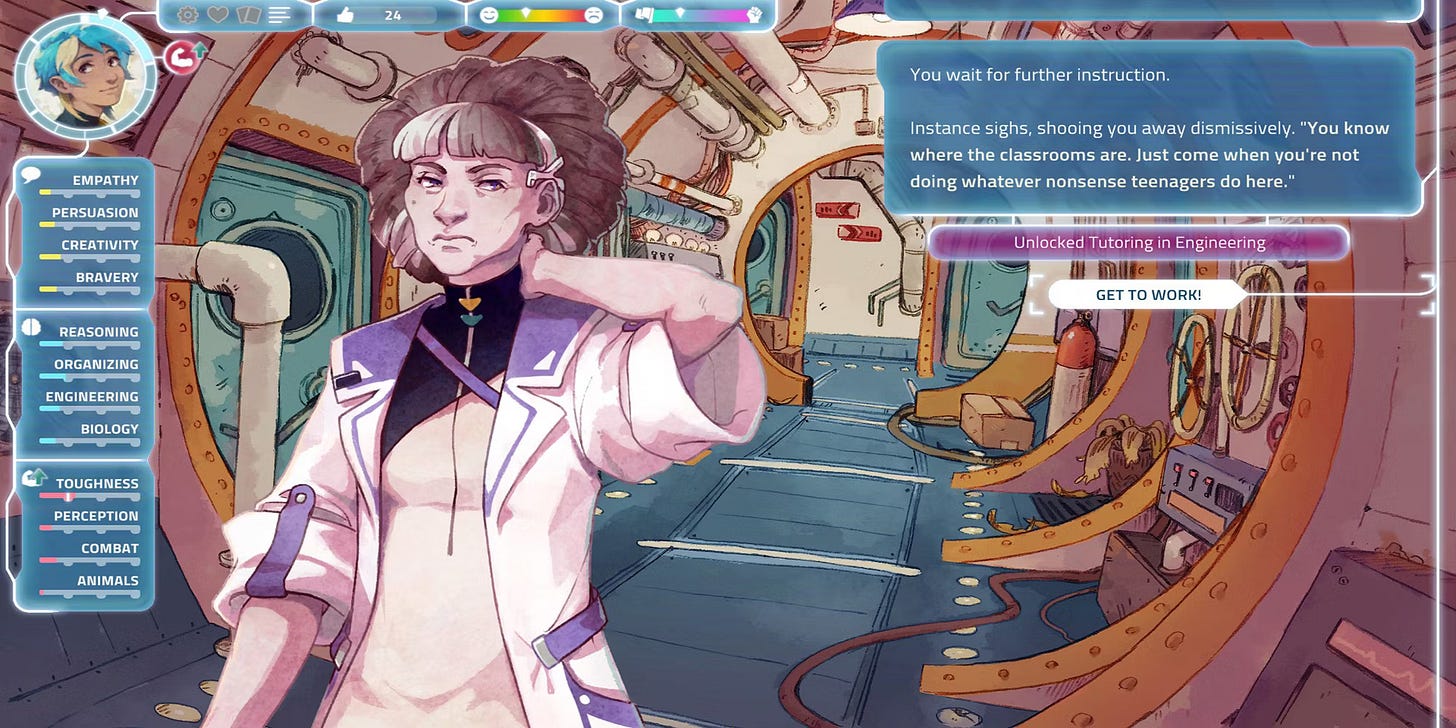

Exocolonist is a game where you grow up on an alien planet. It starts its story when your character is 10 years old, and ends when you turn 20. The story progresses slowly and subtly as you go through this decade of your life. Each month, you choose a task for your character to perform around the colony. Doing this work levels up your skills in relevant areas, resulting in an accumulation of knowledge that is wholly the result of the life you’ve lived. There are several characters who grow up with you, and you grow closer to them based on the tasks you choose (each of them favors a different area of interest) and the conversations that you have with them.3

I decided to play the game “as myself,” making the choices that felt true to me. And I’m a nerd; I always have been. So, although the game reminds you that there are other tasks available besides school, I spent most of my time there, maxxing out the skills it offered (Reasoning, Engineering, Creativity, Persuasion, and Biology). There was another character who spent all her time at school and slowly became my character’s closest friend: a science-minded girl named Tangent.4

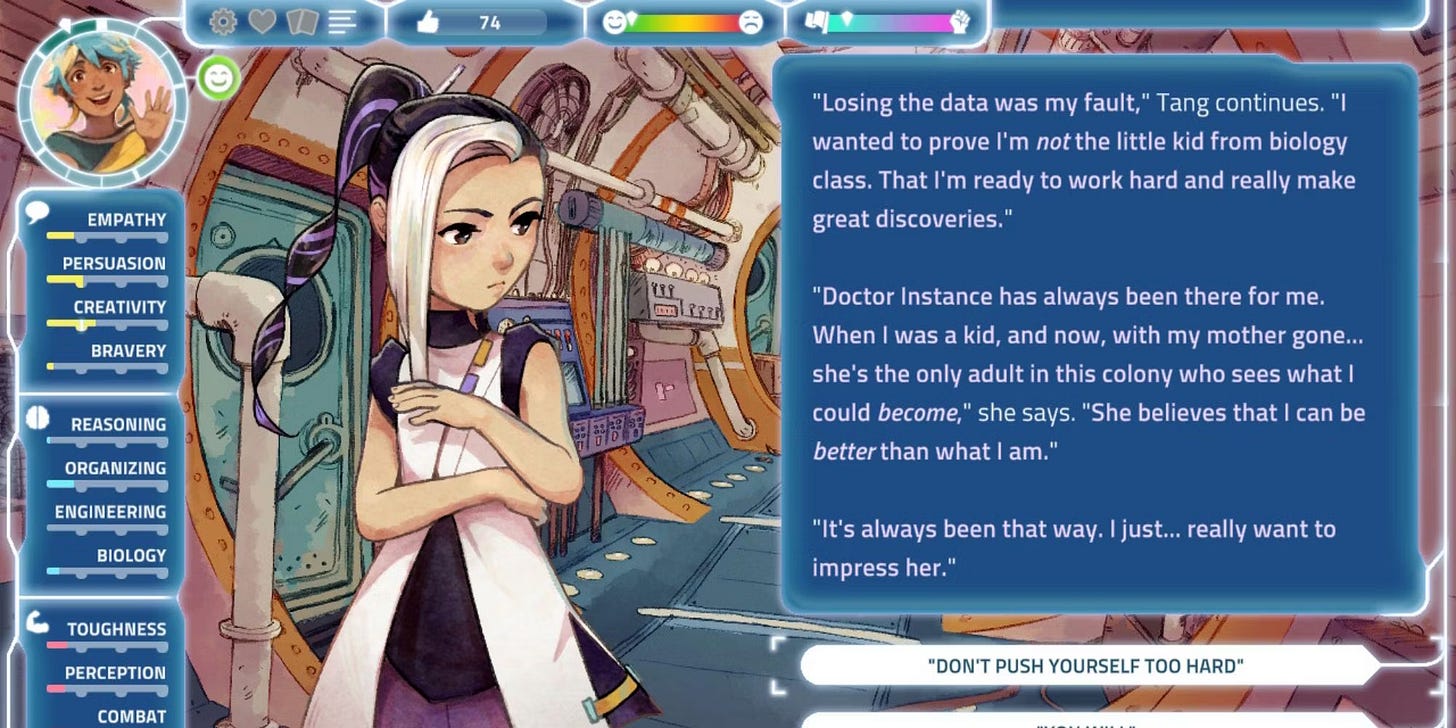

Tangent is a character who was practically designed in a lab to hit me where it hurts. She’s transgender, autistic,5 and somewhere on the asexual/aromantic spectrum (she’s practically wearing the flag), and her story resonates eerily strongly with me and other friends who share those lived experiences. Tangent’s an intelligent child who excels at engineering and biology, but is completely mystified by her own emotions and human connections. She goes through the game with an unspoken goal to make rational sense of everything… and if there’s something she can’t quantify with empirical study, she does her level best to insist that it does not exist.

She’s a ticking time bomb who thinks that she’s the most well-adjusted person here.

Tangent’s mentor in the colony is Chief Engineer Instance, who’s similarly brilliant and emotionally deadened. Instance is one of several relevant adults who hold power in the colony, and one of the least friendly. She’s rude to you and your cohort, and most of her scenes — especially early on — involve her complaining about children. Spending your time in her department will make you interact with her a lot, much to her chagrin.

Tangent is attached to Instance not just as her mentor and her boss, but as a maternal figure. That might sound insane, because it is, but there are a few reasons for it. Tangent’s mother isn’t in the picture due to her own mental health problems. Additionally, Tangent knew she was trans at a young age, and Instance’s futuristic gene-editing software allowed her to transition early and effectively. It’s quite understandable to me why a trans woman would be so strongly attached to someone who accepted and facilitated her transition, especially at such a formative age. From Tangent’s point of view, Instance is an immense improvement from her birth mother in every way, and she won’t hear a word against her.

Tangent spends all of her waking hours that she can in the lab — which is more waking hours than the rest of us, since Tangent is biologically engineered to need less sleep. As she gets older, Tangent seems determined to push past even that limit, subsisting for multiple days on power naps and stimulant drinks until she passes out in front of you. All for the chance to keep working with Instance, who has high standards for her scientific work and expects Tangent (age 10 to 20, I’ll remind you) to meet all of them. Tangent agrees.

You might assume, from my slightly scathing description of Tangent and Instance, that I accurately identified the flaws with their dynamic in the game and tried to make choices that would help them improve it. But… I didn’t see the problem. I agreed with Tangent and, like her, adored Instance wholeheartedly.

Let me explain. My first playthrough took me about twelve hours (I take my sweet time with games!) over several weeks, enacted with monthly tasks and intermittent conversations with the characters. As a simulation of real life, it worked like a charm — the slow pace of life got me to settle into the rhythms, getting to know the characters as their personalities emerged, and mimicking the processes of real-world human relationships. For example, around age 14, another girl, Marz, came out of nowhere and started getting closer with Tangent. My character (and I) felt jilted, and decided that the in-character thing to do would be to snub Tangent in return. After spending a few months hanging out with the other kids, though, I came crawling back. None of them gelled with my character’s (my) personality as much as her.

I mention all this to explain that I essentially inhabited this character, going through the story almost as if I were living it myself. It was an interesting exercise that saw me get in touch with my own emotions and make decisions based on how I felt, rather than what I thought the “right answer” might be. It was almost therapeutic, as I started to have a bit more empathy for myself and the decisions that I made when I was the character’s age. I would recommend it, honestly. But a consequence of that approach is that I wasn’t taking a very analytical view of the characters — I was simply living life as it came, and I didn’t always see the bigger picture.

Your character in Exocolonist has traditional parents: a mother, nicknamed Flulu, and a father named Geranium. They run Geoponics, the agricultural department given the demanding task of cultivating enough food to support human life on an alien planet. (Yes, I know I haven’t talked much about that aspect of the game. I’ll get to it at the end.) It’s a hard job, and while Geranium is an easygoing softie who likes to marvel at the beauty of ecology, Flulu is a bit of a hardass. She works tirelessly to support everybody, and doesn’t have a lot of patience for you when she gets home.

I was immediately fond of Geranium (my own dad is also generally sweet and fond of nature), but I didn’t really care for Flulu. Part of that was due to her callousness, but mostly, she just didn’t remind me of my mom in the same way that Geranium was like my dad. Also, the initial job that you can do with her is literally shoveling dirt, and there was no way I was gonna spend a month on that! So I fled Flulu’s farm and spent my time in school… where Instance lives.

My childhood (in the real world, not in Exocolonist) primed me to associate motherly qualities with someone like Instance. My mom has been a mathematician, educator, and manager for my whole life, and I grew up hearing about her work and seeing it firsthand. She singlehandedly saved my high school calculus class by teaching us a crash course in trigonometry, and helped me wrap my head around statistics in grad school. Growing up, whenever I had a day off but she didn’t, I’d join her at the university and explore the campus — which I would eventually attend in undergrad, and participate in the calculus program she led. In other words, when I wasn’t at school, I just went to a different school. Is it any wonder I turned out the way I did?

As Flulu grew more and more inaccessible to me, Instance was there to fill the void. She’s never exactly nice to you, but if you max out your intellectual skills and make scientific breakthroughs, she admits she has respect for your success. To me, that sounded like love. By the end of the game, my character had, like Tangent, come to see Instance as a replacement mother figure for herself.

I’m trying to spoil as little as possible about the plot, so that anyone who plays the game can experience it like I did. Suffice to say, however, that blindly following Tangent and Instance led me down a dark path. The game gave me so many opportunities to turn away from it, but I missed one after the other. Eventually, after twelve hours of deepening my relationship to Tangent and Instance, doing whatever it took to earn their approval, and making vast strides in science, I wound up with the game’s worst possible ending on my very first playthrough.

Your choices in this game really do have consequences.

The bad ending was so bleak that I immediately rushed through another playthrough in a five-hour marathon, desperately trying to change the characters’ fate. I managed to get another ending (one of 29!) that had an okay-ish outcome, enough for me to feel like I could set the game down. I was still fond of Tangent and Instance in that run, but I kept them at arm’s reach so that I wouldn’t set their catastrophe in motion.6 Satisfied that I’d saved my labmates from suffering, I decided that I’d seen enough of the game to read what people were saying about it on social media.

So I opened Tumblr, and one of the first posts that I saw was an analysis clearly laying out how Instance is subjecting Tangent to emotional abuse, neglect, and isolation.

Oops!

At the risk of running off even further into unpopular opinion territory, I think Tangent and Instance’s dynamic is actually the better depiction of abuse in Exocolonist (which is surprising, because it's not mentioned in the game’s content warnings at all). [Another] relationship is a power fantasy of being a bystander to an abusive relationship; you catch [your friend] when her heavily-armed, hyper-possessive boyfriend with anger issues is giving her the silent treatment once, tell her she deserves better than that, and she’s like “you know what, you're right, I do!” and leaves him and everything is good. Tangent’s is more realistic. You might not even see it unless you really focus and look. [The player character] doesn’t see it, across multiple timelines, even if they’re dating Tangent in some of them. There’s nothing you can do about it; intervening even to echo thoughts she’s brought to you just pushes her away. Tangent is getting an emotional need met there that she doesn’t think she could get anywhere else. That’s more often what it’s like.

— @theomenroom on Tumblr

I felt pretty foolish after seeing this writeup. It’s hard to deny that something is seriously wrong with Tangent and Instance’s relationship, especially when it’s laid out like this. What was particularly harrowing is not only that I didn’t see it as toxic, but I approved of it, encouraged it, and welcomed it. I had helped Tangent to be destroyed by her affection for Instance, and I’d set my character up to receive the same.

When I told my partner about this, she laughed (as did I — it’s funny because it’s so bleak) and offered the most effective summary I could have conjured. “Girl,” she said derisively, “you chose the wire mother.”

There is an adorable character in Exocolonist, Rex, who offers free hugs at all times. He’s extremely easygoing, quick to befriend you, and pivotal to helping the characters work through their emotional issues. When I first encountered him, I saw the option pop up to hug him — and was viscerally repulsed by the idea. I didn’t hug him a single time in my whole playthrough.

Cloth mother, eat your heart out.

With apologies to my real mom, some elements of Instance’s personality and her relationship to Tangent weren’t entirely unfamiliar to me. I’m not thinking of how she acts (which is nasty), but what she respects and stands for. High standards were important for my education, and I’m very grateful that I was always encouraged to employ my critical thinking and creative instincts. But when you combine your parents’ rightful belief in your ability with the school system’s attempts to quantify intellectual performance, a child’s brain has a way of turning reasonably high expectations into an immense level of pressure.

I see a lot of people complaining about “gifted kid syndrome” these days, but I haven’t seen many people acknowledge the cognitive dissonance and duality of the experience between school and home. Everybody I met at school (classmates and teachers alike) treated me like I was some kind of intellectual god-child, existing on a level far beyond their comprehension — even when I didn’t want that, and wanted to be regarded as a normal human. At the same time as I received this endless, alienating adulation, I got none of it at home. My parents knew that I was smart, and they also knew my underfunded public school district was often not advanced enough to truly challenge me. Success at tasks they took for granted was unimpressive. They knew that I could do better than this, and they wanted to know how to help me get to that point. One of my distinct childhood memories is my mom coming home from parent-teacher conferences, exhausted, and sighing:

All your teachers love you, as usual, and no one will tell me any way you could improve.

Now that I’m an adult, I understand exactly where she was coming from. But at the time, I read a lot into offhand remarks like this one. The message that sank in was that perfect was not enough, and that being loved and lauded was not a good or honest thing. Only criticism really mattered. Only criticism really saw you.

Flash-forward a few decades, and it isn’t difficult to see why I interpreted Instance’s disparaging remarks as a sign of a close, intellectual mentorship. Her respect is hard to win, and she required my character to earn it via demonstrations of exceptional intelligence. When she was rude, it was a sign that I needed to keep working. When even Instance was impressed, I knew that Tangent and my character had done a truly stellar job. And so it goes, and so it goes, until complete disaster.

I had a charmed childhood, with very little to complain about — certainly a better childhood than Tangent! — but she and I still turned out uncomfortably similar. Somehow, I came to associate earning respect and love with demonstrating my intellect, and created a dependency. A part of my brain still fears that I can’t have one without the other. I’ve seen that deepseated terror drive me to constantly insist upon my intellect, growing defensive and condescending whenever I think that it’s in question. Even a simple disagreement with a friend can set off my fear of losing their respect, and with it, any hint of their love.

The thing about being a hyper-intelligent nerd kid is that you’re smart enough to fool yourself into thinking your emotions don’t exist, not unlike the 1950s scientists who thought maternal affection was unimportant. But your emotions are still there, even if you don’t believe in them — and the more that you ignore them, the more power they actually have to make your decisions for you.

I’ve realized this about myself. In my first playthrough, Tangent didn’t. The results were horrible for her, Instance, and everybody on the planet.

Let that be a cautionary tale.

That her isolation is because she thinks she’s smart and mature for her age (because she’s being held to adult expectations, and sometimes succeeding) doesn’t make it any less isolation.

— @theomenroom on Tumblr

As I played through Exocolonist, a few recurring themes caught my attention. The game is highly concerned with the environment, and how humans fit into it. The game blatantly acknowledges that the characters are colonizing a world where other life forms — even other people — were already living. A fascist buffoon tries to install himself as dictator, and his incompetence puts everyone at risk when he fails to muster a nuanced response to complex threats. The colony faces a deadly airborne infection, and you find yourself trying to convince characters to wear their masks. On several occasions, a nebulous external danger forces all the characters to shelter in their homes together.

I Was a Teenage Exocolonist is a liberal quarantine novel.

I recognized these themes because not only have I lived them (as have we all), but I’ve also seen them in another book: Bewilderment by Richard Powers. I loved his work in The Overstory, and Bewilderment was his next big novel. I read it in a cabin in the Roan Highlands and was generally unimpressed. Bewilderment is a distilled time capsule of liberal anxieties in 2020, featuring the specters of fascism, pandemics, and ecological catastrophe. In my view, the book hews so close to those anxieties (and their extreme conclusions) that it fails to be anything more than that.7

I didn’t much care for Bewilderment, but something that it shares with Exocolonist is a fascination with alien ecology. The best scenes in Powers’ novel are when his protagonist describes the speculative biology of planets with different orbital conditions than Earth, picturing all the myriad ways life could develop. These wonder-filled scenes are held in contrast to the novel’s bleak events, suffused with the looming dread that human civilization is destroying life on our planet. Exocolonist similarly imagines an alien environment with a great diversity of life, but is dogged by dread that the human colonists will exterminate anything that’s inconvenient to them.8

I was unsurprised to learn that Exocolonist was written in 2020. What I wasn’t expecting to learn was that it was written by a new mother trying to homeschool her children at the same time, but when I step back and think about it, it makes perfect sense. The game’s focus on children growing up under extremely adverse conditions, reckoning with their home’s colonial history and environmental conflicts (in addition to their own worsening mental health!), is an insightful and specific perspective on our current events. Unlike Bewilderment, it isn’t merely navel-gazing about how bad 2020 was — it’s thinking ahead, imagining how today’s children will remember this and be forever shaped by it.

There’s a question at the heart of both Exocolonist and Bewilderment: could things have turned out any differently? Both stories struggle to imagine a better future for us, though they yearn to do so. Bewilderment ends pessimistically — worse, even, than 2020 turned out. The protagonist has no power over human society or the natural world, and can’t protect his son from either one. Meanwhile, Exocolonist encourages you to ask this question by replaying the game, experiencing the story as a time loop. In subsequent playthroughs, your character is able to build on memories from their past lives and take action to avoid events they know are coming. You can try again and again, exploring different aspects of the colony and the alien planet that surrounds it, seeing familiar characters interact in unexpected ways, and striving to make things turn out as best as they can.

We don’t live in a time loop, but anyone who studies history might feel a little differently. One thing that we do know is that 2020 wasn’t the end of it, and we’ll be tested again and again (not least, this November). As we continue to live in a world where our choices have consequences, I’d rather rely on Exocolonist’s hope than Bewilderment’s gloom. We have to believe that we can learn from our mistakes, and do things differently next time. After all, I’ve come to recognize the ways in which I struggle with my emotions, and I’ve slowly started to change my behaviors to healthier ones. I’d like to imagine that Tangent can, too, in a different timeline. In the end, there’s no other option but to keep trying.

The standout visual novels I’ve read lately include Soul of Sovereignty and Heaven Will Be Mine, which both have absolutely stellar storytelling. Their stories also speak deeply to queer and trans experiences, which is something I appreciate about many indie visual novels — they’re unshackled from the stifling constraints of big-budget capitalism and can tell stories that mainstream publishers are too chickenshit to pick up.

You can choose to increase the difficulty of these card games, or remove them entirely if you want to focus solely on the story. I recommend keeping it set to the standard difficulty on a first playthrough for the intended initial experience.

Your character can also romance these characters once you’re all of age. The fact that I didn’t do this — and didn’t even think of it until the game started presenting it as an option — is an effective illustration of my aromanticism.

Before you laugh at Tangent for her choice of name, it’s worth noting that all the characters have strange, futuristic names derived from uncommon words. I eventually discovered that the colony’s most normal name, Cal, is actually short for “Recalcitrance.”

I’m not officially autistic, because I could hold a conversation with the observers in kindergarten, so they chose not to diagnose me. Notably, the people I couldn’t hold a conversation with at that time were other children. Might as well call a spade a spade.

Ironically, I spent more time with Marz, the character who’d tried to steal Tangent from me in the first run, because she’s more involved with influencing the colony’s government.

I also wasn’t thrilled with how Bewilderment othered the protagonist’s autistic son. The novel constantly, unconsciously sets him apart from humanity — whether as an inhuman, bestial thing, or an enlightened mystic who’s wiser than everybody else — and seems uninterested in ever exploring his own interiority. Contrast that to Exocolonist, where the narrative lets Tangent define herself on her own terms, the same as anybody else.

I always have to push back against simplistic ideas of humanity being inevitably destructive (which is more present in Bewilderment). The western left has a tendency for our criticisms of society to devolve into liberal handwringing, ascribing the failures of our civilization to everyone as “human nature.” These notions are probably brought on by the culturally Christian theology (baked into our culture, even if you’re atheist) that primes us to view humans as sinful creatures, set above and apart from nonhuman life as stewards. A better view would be to recognize that we are evolved, living organisms like everything around us, simply following the incentives that the world presents — but that we have the power to structure our own incentives. For an insightful essay on the self-centered undercurrents of much western environmentalist thought, I recommend William Cronon’s influential essay, The Trouble with Wilderness.